MUHS Senior Soundwaves

Dano–Your essay below is the inspiration and the catalyst for everything to follow in my blog. So you get the credit (or the blame–hahahaha!) no matter what the hell I post in here! Seriously, when you initially wrote your essay about 5 years ago, it brought back a flood of memories and made me examine a life for which I am truly grateful. Not only in the sense that I remembered the things we did together (like playing in a band and sharing a high school experience together), but I immediately realized I had dozens of similar life stories I wanted to tell about what I’m calling my “55 rock star years” on Planet Earth. I started making a list of my life stories on a legal pad whenever I thought of them, and I’ve amassed at least several dozen at this point. Now is the time to express my gratitude for this awesome life and hopefully inspire others to realize how lucky they truly are…

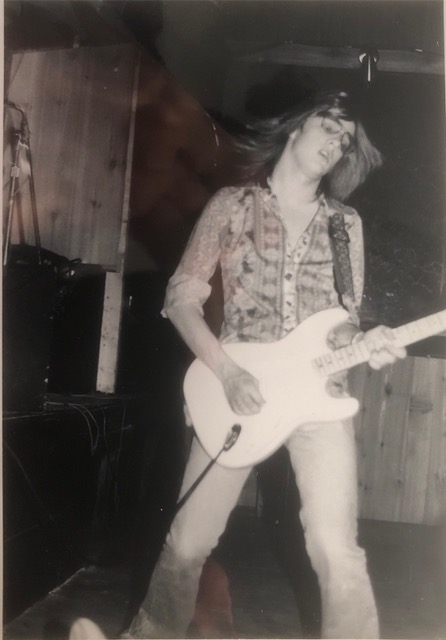

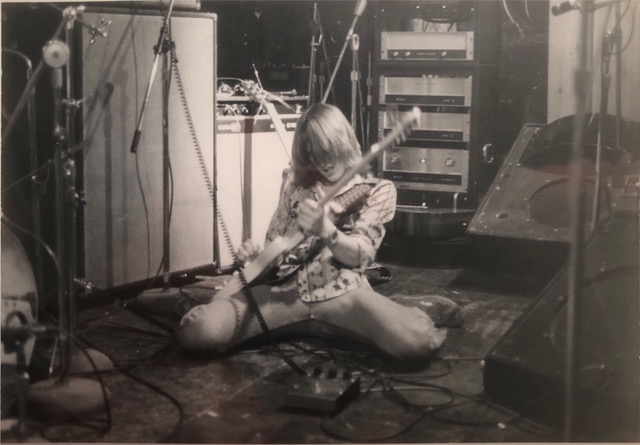

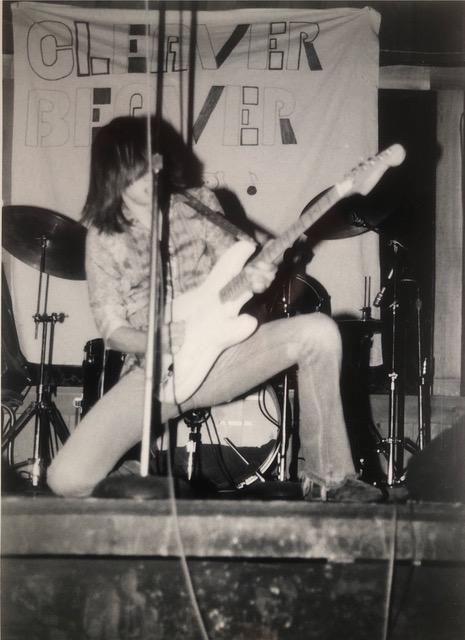

“Crickey the Rock Star” (OK–I was never a real rock star, but it sure was fun “playing one on TV,” especially with you guys!

Crickey

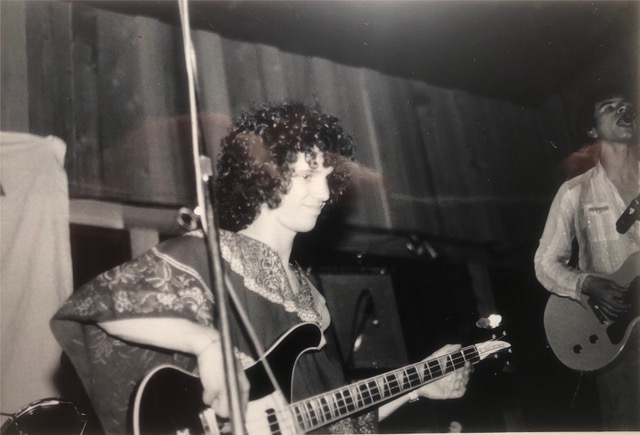

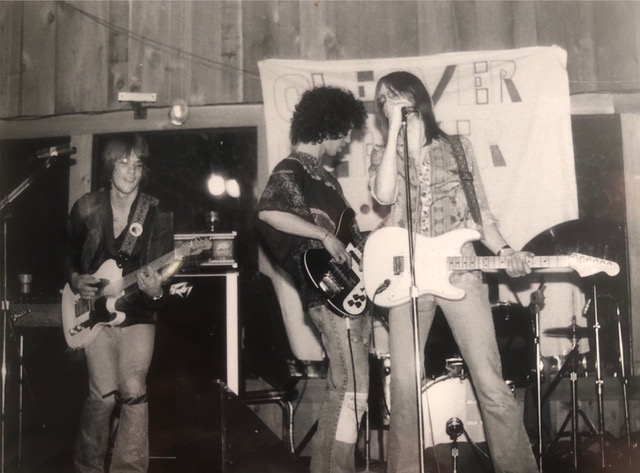

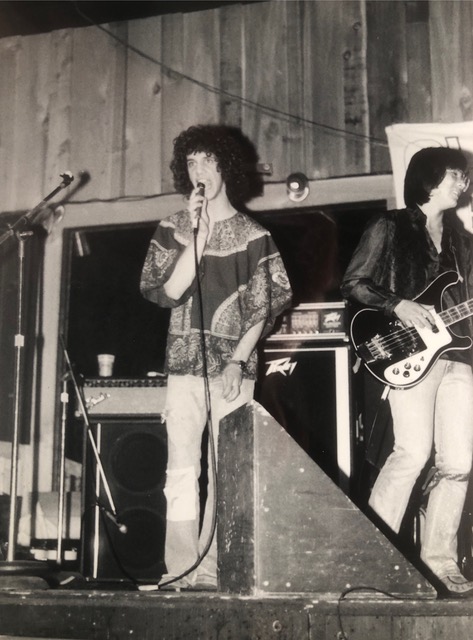

Bucko on Bass

Bucko & Dano

Like our homemade band signage?

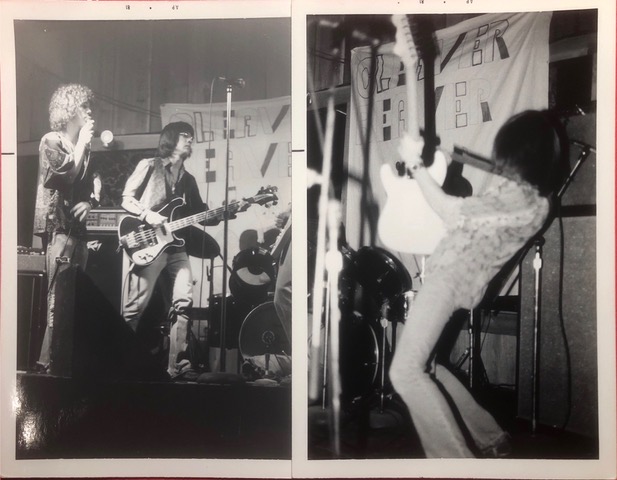

Bucko & Crickey

Bucko & Dano

Senior Soundwaves: 1981 Overture

by Daniel K. Kim

I quietly strummed my guitar. It’s hard to do that when you’re all amped up, on a stage, and seconds from beginning a show. I knew I wasn’t supposed to, not yet, but I had this dreadful feeling something was wrong. Strummm…it was out of tune. Every. Single. Fucking. String.

In dreams, once you find yourself naked and in front of a crowd, you wake up. That is the difference between a dream and a nightmare, and there was no waking from that moment. A quick tuning of the guitar isn’t that complicated, but when you don’t have a starting point and you need to be in tune with your band mates, it gets complicated real fast. “Fucking road-eyes. Buck, give me an E,” I said to the bass guitarist.

The stage lights were still off, and the high school auditorium was dark so I couldn’t gauge the attendance. There were over one thousand seats, and it was surprisingly packed for a high school gig. It was “standing room only” packed we learned later. Every year, seniors would play in what was dubbed Senior Sound Waves. That year, it was subtitled ‘81 Overture’ and the poster had an apple shot through with an arrow. Buck was in charge of promoting the show. No doubt, it was he and the Roach who tied our 1981 graduation year to the William Tell Overture, hence the arrow and apple. Buck’s idea of promoting the show consisted of a promise and a flyer.

The teacher in charge of the event, Mr. O’Neil, was young and enthusiastic enough to believe Buck’s promise that the show would sell out at $5 a ticket. Buck then printed out a bunch of flyers, pinned a few up around the school, and then gave the rest to his girlfriend K.A.A. (pronounced ‘kaw’, as if you were imitating a crow call) who attended the sister all-girl school. We thought there was somewhere between nine and twelve hundred kids and parents. O’Neil was ecstatic. K.A.A. had come through.

The crowd sat expectantly. That was the worst part. I felt that everyone stopped what they were doing just to watch me. To listen to me. To see if I could tune a fucking guitar. To watch, and to listen, and to see me fail. My hands began to tremble. If I had my own guitar, this would never have happened. This never would have happened to Jimmy Page. Jimmy had his own guitar, and plenty of them. He had that sunburst Les Paul; the double neck electric; the acoustic; the double neck acoustic; even a goddamned triple neck acoustic. Jimmy had people and they tuned his guitars. Jimmy had roadies, not road-eyes like I had. And, other than the fact that Jimmy wrote million-dollar songs, sold millions of albums, owned a castle in Scotland, and could hold an entire arena in awe with his mastery of the instrument—playing it with a goddamned bow for Christ’s sake—the only real difference between Jimmy and me was the fact that he had long curly hair. Mine was straight. Well, that and that I had a pack of stoned and drunken road-eyes chimping around with my guitar…and that it wasn’t even my guitar.

Back around ’74 or ’75, I rescued an abandoned catgut string guitar from my eldest sister’s closet. I had no idea how to play, but I knew instinctively that I could. My older siblings—sister, brother, sister—were each forced to play an instrument. They could choose their instrument, but not whether they would take lessons. I loved a picture of my brother when he was eight. He was frowning as light reflected off the coke bottle glasses he wore. He had a mop of cow-licked hair. He was sitting on a fold-up chair being crushed by an over-sized accordion; his chin barely reached over the top. Soon after that photo was taken, mom relented and he took up the trumpet.

My second sister played the clarinet. Sometimes, when she wasn’t around, I’d open the case. The body of the clarinet was mesmerizingly smooth. It was jet black and had silver keys that hovered an eighth of an inch over the holes. I couldn’t help but touch it. I knew I shouldn’t, I had been warned. I just couldn’t help myself. I couldn’t get one goddamned sound out of it, though, other than a squeak. No matter how many reeds I jammed into it, no matter how many sections I took off it, or twisted around, or tried to rearrange the order of, nothing made a difference. In the end, I would pretend and simply hum through the bottom, bell-shaped section.

It was my oldest sister’s guitar. They took lessons at Maus Music. I was too young, they said. In time, I was assured. I recall walking on the creaky wooden floor of the store as they took lessons in small rooms closed off by musty smelling curtains. I bided my time by looking at the cymbals and triangles and other instruments hanging on the walls. I would thumb through sheet music all wrapped in plastic and arranged in long, wooden racks. I couldn’t read any of it, but I could dream. One time, Mrs. Maus gave me a kazoo.

Something unusual happened, or should I say, didn’t happen when I turned eight. I wasn’t ‘forced’ to play an instrument. My mother had died, and my father, who was naturally a “Sit down, shut up, and study your lessons,” kinda father, simply had no patience for the unique racket my siblings made. Whenever they practiced, the house sounded like a grade school orchestra gone rogue; random notes flitting about, intolerable squeaks, and I swear every song died from arrhythmia. It was as pleasant to listen to as two fully laden glass trucks colliding with one another. When my time came, I was practically forbidden to play. But I did anyway—my sister’s old catgut guitar.

It took a couple of years of me begging, and the help of my step-mother, Diane, but my father finally relented. I was allowed to purchase a steel string guitar. It wasn’t some grand gesture on his part, more of an embarrassed acquiescence. There was more of a ‘you can play it in the basement when I’m not home’ feel, than a thoughtful gift meant to show confidence in my budding talent. “Beethoven could play any piano–He didn’t need a grand,” Dad said. None of that mattered though. I had my guitar and he was never home.

One hundred bucks didn’t buy much of a guitar. I kept the receipt in the cardboard case the guitar came in. It was a quarter-body sized Epiphone with a spruce top and mahogany body. I called it Epi. I felt like a troll playing a ukulele. It had something of a dreadnought body, but I always thought the body top—where the neck meets the body— was disproportionately small compared to the body bottom—the part you drape your arm over. I couldn’t sit down, put both arms over the top of it, and talk with whomever was in front of me without severely listing to my left. Normally that wasn’t an issue, unless I happened to have a few drinks or accidentally inhaled something—then it became problematic. My only hope was that any drug induced lean was to my right, then the guitar would actually hold me in a neutral position. The Epi produced a sound something like those iPhone-sized Japanese transistor radios from the ‘60s, and the B string was impossible to tune. I had to file the bridge down to lower the action so my fingers wouldn’t bleed. Of course, lessons did not come with the deal.

The key to our show was the trap door, and you must understand this point. Buck came up with the idea (I think he did, but he doesn’t recall). A typical high school band would subject their audience to a series of crashing drum cymbals, ear splitting feedback, and an endless, eye-glazing string of “test, test, tests” as they set up their equipment. After which, these amateurs would hack out a few cover songs, and then float from the stage on their over-inflated egos. We, on the other hand, intended to put on a show. I had visions of lasers dancing to Baba O’Rielly as an act opener, but I quickly shot that down myself. Who had lasers? Who could play the keyboards? Who was going to sing like Roger Daltrey? The Who, that’s who. No one else could possibly pull that off.

No, we needed a dramatic entrance, but, one that could work. We decided to have the trap door slowly raise each one of us, one at a time, and under dim lights. Then, the hooded road-eyes would carry us to our respective spots on the stage as if we were mannequins, or something. Then they were to hang our guitars on us. Of course, that meant entrusting my guitar to someone else, if only for a moment. I think my road-eye was drunk. I think he crashed my guitar into every wall between the dressing room below and the stage above. I think he dropped it down the steps a few times. Heck, I think he skateboarded it down the steps. I think he hated me. But, this wasn’t truly my guitar. This wasn’t the Epi. We were electrified. This was some nameless imitation Telecaster on loan from Tow Head.

Tow Head was of elfin blood; slight figured, white skinned, anime round blue eyes, and long blond hair that clung close to his head. He was a bit squirrely, and a reluctant student in freshman English class. Fr. Forey, a frock and sandal wearing Jesuit, who could easily have passed for ‘long since dead’, dubbed him Tow Head in a moment of bewilderment at some off-the-cuff answer the Tow Head once proffered in class. Fr. Forey himself had long, thinning, grey hair and a beard that he could chew on if he was ever so inclined. Though I never saw him do this, I often imagined that he did. He reminded me of Merlin. If you were dark haired, he would call you a horse’s collar. To be stumped on a vocabulary word was an affront. “That’s a good word,” he would sullenly say. “Learn it, put it in your pocket and use it…you…you horse’s collar!” Tow Head knew that he wasn’t going to play in the Senior Sound Waves, so he lent me his guitar.

Someone in the crowd shouted “Dan-O.” Buck had helped me tune the E, A, D, and G strings, but bass guitars only have the four strings. I was on my own for the B and high E. The cheapness of the Epi had damaged my ear. To this day, I cringe when trying to tune a B string—it’s one of the reasons I gave up the instrument altogether. Since one naturally uses the B string to tune the high E, I had to adopt alternate methods. I used harmonics to tune the low E and the high E together. It sounded cooler, and made it look like I knew what I was doing. But, that left the B to total guess work.

My first attempt at electrification came at the expense of my family. We had an old Garrard stereo cabinet as large as a buffet. The outer doors hid the speakers. The inner doors covered a reel to reel tape deck, space for albums, a turntable, and the control panel. I would plug the jack-end of one of those cheap four-inch, black plastic microphones into the control panel, and then jam the head-end of it into the body of my acoustic guitar and crank up the volume. There was a lot of feedback, and you could hear the mic banging around inside the body every time I moved and I moved a lot. I had to.

In order to figure out songs back then, I had to play a small segment of it on the album, lift the needle up, and then try to imitate what I had heard. It was a painfully slow and repetitive process, especially if there was complicated finger picking involved. My brother simply said, “The louder you play, Dan, the louder your mistakes are.” I was a bit downtrodden after that. I had reasonable talent on the acoustic guitar—I just never developed the corresponding confidence to pull off a one man show. But, then came the call.

Our original band, The Derek Small Band, was the brain child of The Stiff (that wasn’t his real name, but given that he stiffed me on a business loan later in life, I feel tagging this label on him appropriate.) Back then, I had no idea who—or possibly what—a Derek Small was, but that didn’t matter. The Stiff said it was a spoof, and had something to do with Jethro Tull. Of the twenty-six members of Tull, none of them were named Derek or Small. Recently, Buck informed me that Derek Small was the name of a fictitious character on the cover of Tull’s Thick as a Brick album. Sometimes, I just wanted to beat the Stiff like a drum. Anyway, back then it didn’t matter. What mattered was getting a band together and jamming. Tommy played drums, Buck was on bass, I played rhythm, and Stiff played lead and sang. Everything was based on Neil Young’s Live Rust album and movie. Even the cinnamon colored, cloaked and hooded, Jawa looking, road-eyes.

For this gig, Senior Soundwaves, we brought on a special guest, Crickey. Crickey could play the guitar. Though our decisions were made in the fog and smoke of adolescence, many–surprisingly–turned out to be right. The decision to bring Crickey into the band was one of them.

Stiff was something of a bigot, which was odd given that he was full blown Mexican. My Korean side had shown me the harm of bigotry long before. I was always the Chink, the Nip, or the Jap or whatever because none of the pasty-faced blondes at the parochial grade school I attended knew where Korea was let alone any derogatory slang specific to the country. The Stiff’s racial slurs were threatening to become the focus of the band.

Crickey, on the other hand, was somewhat anomalous. He was tall, thin (a bit pasty himself), but didn’t care at all what you looked like as long you thought right. Idiocy was his biggest -ism. The amount of weed Crickey smoked would make most men curl up in a fetal position, claw at the air, and shield themselves from people they knew were coming after them. Pot can have this paranoia inducing effect on people, or so I hear. But not Crickey. He scored in the top 3% of the nation on his ACT and SAT tests while stoned out of his gourd. He was a critical thinker, and loved to argue with authorities. But, more than anything, he could play the guitar. He taught me the scales and how to find the chords within them. With his help, and a Mel Bay’s Book of Guitar Chords, I was able to start figuring out songs for myself. By bringing Crickey into the band, we refocused on the music.

I drove the bandmates insane at practices with my propensity to throw in ‘Wacka-chucka’s at inappropriate places. I couldn’t help myself. I loved them. I was a Wacka-chucka-holic, in total denial, and in need of an intervention. A Wacka-chucka is something akin to a muted ‘Fiebrantz’ and best played in an empty, otherwise silent space, known as a rest. To put it simply, form a chord, but then mute all the strings with a free finger, and strum down. That’s the Wacka. The ‘chucka’ is the partial up-stroke on the strum. Once you know what you’re listening for, you’ll hear them a lot. Jimmy loved them. He used them to great effect in The Ocean. A full-blown Fiebrantz, on the other hand, is its opposite. The ‘Fie-’ is a partial up strum and the ‘brantz’ is a wild hack of a down strum. Instead of muting the strings, you let a discordant chord ring out.

One practice, they took me up to a bedroom in Tommy the drummer’s house. They sat me down. It was a small bedroom inside a small bungalow on the south side of Milwaukee. No words were spoken. I felt mildly claustrophobic. The bed had a white cover. Dirty clothes, lying on the floor, kept the closet bifold doors from closing. There was a turntable, the type with a built-in speaker, on a table in the corner. The speakers crackled. Soon, the song we had just been practicing broke the silence. They forced me to listen to it. Crickey kept repeating, “There, that’s where you Wacka-chucka, right there and nowhere else!” I felt humiliated. At one point, Tommy the drummer had to leave the room. The mirror hanging on the wall was of no use. I needed to look deeper. I was forced out of my denial. And, with the support of my bandmates, began the long and lonely walk down the road of Wacka-chucka-holism recovery.

About the only thing I loved more than the Wacka-chucka, was the technical lexicon used in the world of high school garage bands.

The first thing we decided to do, was to rename ourselves. Actually, it was about the fourth or fifth thing, but, whatever. The Derek Small band had played out once, a charity gig at some Catholic school. We were well received, but it was time to move on. We were sitting around the kitchen table at Tommy the drummer’s house on the South Side. You couldn’t be in the South Side without over spicing the conversation with ‘hey der,’ ‘ya know, hey?’ “wanna PBR?’ and ‘how bout dem (you fill in the blank.)’ Of course, ‘kielbasa,’ was pretty much the answer to any question posed. Those who mock Wisconsinites’ vernacular, always sound like Southsiders. Think Fargo.

The term South Side became pregnant with so many other words and concepts; we simply called South Siders ‘hey-ders.’ Tommy was a multi-generational hey-der and took pride in the car up on blocks sitting in his driveway. He worked on it over the weekends. All good Southsiders had a car up on blocks and a six-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer on ice. He lived just north of Cudahy. Cudahy, the meat packing company (hence kielbasa), epitomized all things southside. Personally, I just liked the way the name contained a natural echo…’Cudahy, hey.’ So, we were sitting around the kitchen table, talking like a bunch of hey-ders, as we set out to rename the band.

My sisters were members of the pom pom squad at their high school. Pom pom girls were like cheerleaders on steroids. They held themselves to a higher standard and were adored, or loathed, by the crowd. It really depended on whether you were on the squad, or everyone else. There was arrogance and cattiness. Some thought the whole thing so ridiculous they referred to the squad as the pompous pompous girls. Often, practices were held at our house. It drove me nuts. What seemed like hundreds, maybe thousands, of girls would descend upon the house screaming and doing all that girlie-girl hugging crap. I swear if they practiced at all I never saw it. Yet, at half time of every game, they would strut onto the field, or court, in their short little skirts, pompous pompous poms bouncing, plastered on smiles, and dance a dance they called the Highlander Fling to a song called Scotland the Brave. Watching them was okay. It was the song that kept my attention.

There’s something about bagpipes that lifts me to a higher plane. Listening to bagpipes is like eating a cumquat. Cumquats are micro-oranges inside out. The rind is sweet, but the meat is bitter. You pop the whole thing into your mouth and eat the rind, the meat, and even the seeds. At first, it tastes good, like you made the right food choice for the first time in your life. But, that doesn’t last long once the juices start flowing. When that happens, your face pinches up. Your body shudders. I swear to God, the first time I ate one, I asked, “Are you trying to kill me?” But, then I reached for another. And then, another.

It took time, but I figured out how to play Scotland the Brave on the Epi. I had to re-tune my guitar to an open G tuning, so I could get a nice constant drone like the bagpipes have. That freed up my left fingers for playing the melody. I thought it sounded pretty cool and that thought was what struck me when we were sitting around Tommy the drummer’s house talking like a bunch of hey-ders.

Crickey and Buck were at the breakfast table. Tommy sat on the counter and the Stiff was hovering about. I sat on an upholstered chair a few feet away and had been dreaming about I thought Jimmy would be sitting if he were sitting in this chair inside this southside bungalow. But then, the vision: Scotland the Brave–electrified. The song would begin with a dramatic prelude: a long drawn out, seat-rattling droning in the key of G; multi-colored spotlights slowly illuminating and circling a mist filled stage; a lonely, fuzzed-up guitar slipping through the darkness. It would be haunting, think loon on a moonlit, woodland lake. Then, in a few bars, the lights would blare and the rest of the band would crash in and the song itself would begin.

Brilliant!

So, I said, “How about Bagpipe Music?”

The phony hey-der accents stopped. I was met with blank stares. Silence, himself, paused to look. A chair scratched the floor as someone shifted in his seat. They simply couldn’t access the wonder and awe of the scene inside my head. I blame them not. Slowly, the scene vanished like fog burned away by the midday sun. My head was empty, and I felt cold and alone. A solitary seed in a dried-up gourd. The once brilliant idea, slowly and painfully, came to a rattling end, leaving me to wonder, what if I had offered up The Cumquats instead?

The subject of sex was never far from the mind of a teenager, and so it was no surprise that that was what filled the vacuum created by my suggestion. The best way to get a laugh out of a teenager is with a sex joke. Someone cracked wise to break the tension. ‘Beaver’ was a big term back then when referring to a woman. And we all grew up watching Leave it to Beaver. Cleaver had become the pivotal word because–as Crickey explained his thoughts–it phonetically sounded like “cleave her.” Right there and then, The Cleaver Beaver Band was born. There was only one problem; the Jesuits who ran our school were smarter than us. We knew the name would never fly. We decided to ‘put that name in our pocket’ and use it for future, non-Jesuit, gigs.

We sat in silence for a while. I had read the book Equus in English Lit and we also watched the movie in class. It’s a story about a messed-up kid running naked in the night blinding horses with a spike all the while shouting, “He sees you, He sees you!” I couldn’t help but think, “Of course He sees you—you’re running naked in the night blinding horses with a spike, for Christ’s sake.” Since our show was a total rip off of Neil Young and his band Crazy Horse, we decided to play with the name. We were armed with the Latin word for horse, equus, all we needed to find was the Latin name for crazy. The Stiff knew the Latin teacher—a tall geeky guy whose only possible lot in life could have been a high school Latin teacher—so, it was the Stiff’s job to find out the proper Latin word. A few days later, we became Equus Daemons. Not only was the name fitting, it was sure to impress the Jebbies.

The show was broken down into segments. First, we all played together; a few Stones songs and one Dylan. That was the fun part. Buck couldn’t play bass and sing at the same time, so I got to play his Jet-Glo Black Rickenbacker 4001 bass on the songs he sang, like Live With Me, Get Off My Cloud, Jumping Jack Flash, and, of course, Sympathy For the Devil. For some reason I’ll never understand, while Buck couldn’t sing and play a four stringed instrument, he could jam on the piano and sing without a problem. The Rat Rickie, as he called it, had this full bass sound, but with a bright tonal quality. It could really shine through the full force of a cranked up, fuzzed up, curtain of music. Live With Me was my favorite. I started off the song, and for a few bars, it was just me. The same was true for Dead Flowers. Except, on Dead Flowers, not only did I start out the song, I actually used my own acoustic guitar. I couldn’t sing for shit, though. To quote Leo Kottke, my voice sounds likes goose farts. I was given the task of ‘who-whoing’ my way through Sympathy, and was the response to the call in Get off My Cloud.

After the Stones and one Dylan segment, everyone except Crickey exited the stage. He stayed on and played The Star-Spangled Banner ala Hendrix. He had this white Castillo, a Japanese rip-off of a Fender Stratocaster, which is what Jimi played. To watch Crickey, you’d think Jimi had been reincarnated into a pasty white suburban kid. At some point during his performance, I believe when he played with his teeth, Crickey cut himself. There is nothing as poetic as red blood dripping down the face of a white guitar as it bleeds out the Star-Spangled Banner. Of course, some of the folks there said it was blasphemous to play the song that way. They were probably old and white and had never heard of the young black man named Jimi. Crickey played behind his back. He played with volume. He played on his knees. Then, he collapsed onto the stage and let his guitar ring out with such dissonant discord, it eventually turned into a deafening hum of uncontrolled feedback.

The Stiff walked on stage with his acoustic. He was going to do a few solos. Neil Young. That was the start of the Neil Young part of the show. As he walked out, he dropped a black rose onto Crickey’s dead carcass as the road-eyes prepared to drag him off stage. Fr. Stang greeted Crickey right behind the curtain.

Fr. Stang was hairy and sloped like a Neanderthal. To some, he was The Missing Link. To others, he was The OranguStang. Out of naked fear, I called him Fr. Stang, my physics teacher. I saw him a few years ago, back at that school. I was visiting, and caught a glimpse of him down a hallway. I couldn’t be certain, though. It was all a blur. After gathering my courage, I went for a closer look. He had disappeared. Vanished. No trace what so ever. His hair was still long, but white. He still had that Neanderthalian slope. The Missing Link had become Yeti. The receptionist confirmed my sighting, but said no more.

In his prime, Fr. Stang had an egg fetish. Once, he made us wrap up eggs so that he could drop them off the roof of our four-story school. After that, he lined us up in the gym, two rows facing each other. One row was given eggs, and told to throw them at their partners in the facing row. It wasn’t like dodgeball or anything…at least it wasn’t supposed to be. I mean, after all, what could possibly go wrong if you give a group of teenaged boys dozens of eggs and tell them to hurl them at one another? We were supposed to throw, catch, take a step back, and repeat. The point was to see who could throw and catch the farthest without breaking the egg. Why that ever amounted to a point I’ll never know. I’m not sure anybody won either of those competitions. Certainly not the janitor.

Fr. Stang had no sense of humor. One day we got back from a liquid lunch and took our seats in his physics class, the last period of the day. His head jerked upward, he emitted threatening chimp-like grunts as he slowly sniffed the air. He glared. “It smells like beer in here,” he said.

I am positive we would all have been busted and expelled if good ol’ Murph hadn’t jumped on the hand-grenade. Murph smirked, jabbed a thumb over his shoulder in the direction of an open window and said, “That’s because Miller Brewery is right there.”

It was. You could see the red Miller sign high above the main brewery right outside our window. On windy days, the smell of hops filled the room. But Fr. Stang didn’t smell hops that day and wasn’t about to take any nonsense from a curly haired, bobblehead drunk like Murph. I think he is still in detention. God bless him, though, he saved us all.

Mr. O’Neil was in charge of this show, however, the auditorium belonged to Fr. Stang. He was not there, though, the day we mapped out our show. Unfortunately, he was there as the road-eyes dragged Crickey offstage. He thought Crickey had actually died, or passed out from an excess of drugs or alcohol. It was almost a showstopper. I was on the other side of the stage behind the curtains. Crickey was known to drink, but he didn’t that night (except for that medicinal, half bottle of Jack Daniels—but I wasn’t witness to that.) As the Stiff began playing “I am a Child,” Crickey told Fr. Stang that he was fine, it was part of the show, didn’t he see the rehearsal? and, that he should go and leave him alone because the show wasn’t over. There was a stare down, Cro-Magnon versus the Neanderthal. Evolution rendered her verdict, and Fr. Stang silently slipped away to where his lair lay. The show went on.

We all met in the dressing room beneath the stage, while the Stiff did his thing. He was singing Sugar Mountain or some such song, we sat tuning up and generally being very quiet. The worst part about performing live is the wait. I had vicious stage fright. I felt like an early Christian as the Roman Colosseum announcer introduced the lion. Waiting to step onto the stage only to be scared out of my wits wasn’t exactly what I thought of as fun. I kept thinking about the Cat. The Cat was the debate and forensic coach. I wasn’t a member of either team, but, he also taught the Speech and Debate Logic courses, both of which I took. He said to wiggle your toes if you’re nervous because no one ever looks at your feet. He said never to fold your hands in front of yourself when standing and addressing a crowd because it looks like your hiding something, like a boner or a pee stain. He said to adjust your cuffs, assuming you’re wearing a suit, because it looks like you are meticulous. He said ‘Bust!’ in his ridiculously high-pitched voice every time he stepped into the goddamned bathroom because we were always smoking cigarettes in there. He said a lot of things, none of which were helping me with my stage fright. But, I do know that my guitar was tuned by the time Stiff was done singing, and the trap door was lowered.

The idea was for the band to rise up onto the dimly lit stage, one at a time. Then, the road-eyes would carry us to our spots. Mine was stage right, in front of a stack of amplifiers. Buck came next and was stage center-right. Then came Tommy the drummer, he was stage center-rear, Crickey was stage left, and Stiff was already there in the center.

The road-eyes were supposed to have rigged up small flashlights inside their hoods to help them see around the darkened stage and to make them look like the Jawas in Star Wars. This was a direct rip-off from Neil Young’s Live Rust tour. They couldn’t manage the task. Their hoods were too small. Their flashlights were too big. They weren’t exactly the road-‘eyes’ we had envisioned. Lenny, the Roach, and Moys were the road-eyes. I don’t recall which two carried me over, or who gave me Tow Head’s guitar, but there I was, nervous as all hell, cursing, and begging Buck for an E.

One thing about the Stiff, aside from being financially irresponsible and a bigot, he could play Neil Young better than Neil Young. Neil Young had extraordinary song writing abilities, but he was pretty much a hack guitarist. Stiff figured out each note of every song, then smoothed out some of the rougher edges. He played a 1958 Les Paul Jr. He called it a Les Paul TV, and said the TV stood for Tone and Volume, because it was the first model with tone and volume controls mounted on the body of the guitar. In truth, its color was referred to as T.V. White. The guitar itself was beige, but on a black and white T.V. it looked white. The same model was used in a Happy Days episode when Ritchie was in a band. Either way, it had amazing harmonics and the fullest sound I ever heard. But, until that night, I had only heard it through practice amps, or other small amplifiers.

The amps I stood before that night were part of a professional grade sound system run by a trained team hired by the school specifically for this event. Mr. O’Neil, the teacher in charge, saw to that. He was young, and wore a beard and mustache. He was cool. The auditorium itself was not rigged for microphones and speakers. It was designed to be acoustically perfect, and built for putting on plays without the need for microphones. That night, we played through a tri-amp sound system, with Altec-Lansing “Voice of the Theater” speakers. It had two, seven-foot tall 3-way amp stacks—one on either side of the stage. Several smaller foot monitors, interspersed between the foot lights, faced inward and were supposed to enable us to hear ourselves. Until you’ve stood next to a seven-foot tall, Altec-Lansing amp stack cranking out rock ’n roll at full volume, you simply don’t know the meaning of loud. Those foot monitors may have been blaring The Sound of Music for all I knew.

Sound is a wave—a disturbance that travels through a medium. Music is sound. Music was my life. Waves I breathed, dreamed, and bled. The bars of a staff measured my days. The sound that came out of that amp stack was a sound that cannot be reproduced by any stereo, or any headphone set; the depth of the bass, the richness of the midrange, the slicing trebles waxed in harmonics. The sound travelled directly through me, it tuned me, so that my body vibrated in synchronicity, thereby amplifying our music even more. I felt husked, and my fragile soul laid vulnerable on that stage. I could feel my brain squirm—and I wanted more.

Once my B string came into tune, I gave the signal. The spots shone brightly. The Stiff played the opening notes of Like A Hurricane. The crowd began to roar. We were a group of kids, and we called ourselves Equus Daemons. I was a part of that. I knew I was the least talented of the group, but that didn’t matter. For one brief moment, on a February night in 1981, I was the music, I was the medium, I was a sound wave.